My last post introduced viscoelasticity. Today’s post will cover one of the phenomena of viscoelasticity: creep.

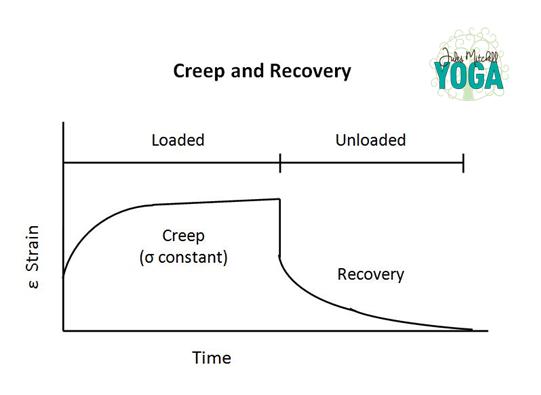

Creep is defined by an initially rapid increase in strain (deformation) followed by a slower increase in strain at a constant stress (load) over time . Simply put, some materials continue to elongate when stretched even when you don’t continue to increase the force of the stretch.

For example, gummy worms exhibit creep. I have referenced these candies before in my post on stretching range because of their viscoelastic properties. If you stretch a gummy worm, at first it elongates quickly, but then it continues to elongate even if you don’t pull any harder. Said another way, the rate of elongation slows, but it still continues to elongate. For math and science peeps, this means the relationship to strain (deformation) over time is non-linear.

Creep is a reversible phenomena. Once the load is removed, the original shape (or length in this case) is recovered. This is called…recovery. Recovery is not instantaneous and is also a function of time. After you stop stretching a gummy worm, it will begin its recovery and eventually return to resting length.

Unless you’ve stretched it beyond its elastic capacity…

Collagen fibers (a primary constituent of our connective tissues), because they are viscoelastic [1], also exhibit creep and recovery. That means that under a constant load, like gravity, the fibers will continue to elongate. When the force is removed, the fibers will recover.

Unless the fibers have elongated into the plastic region…

I often hear yoga teachers talking about the importance of stretching tendons and ligaments to improve flexibility. It provides a false notion that stretching these tissues will somehow make them longer. When elongated, tendons and ligaments will either creep and recover (i.e. not get permanently longer) or get long enough to plastically deform (i.e. damaged fibers).

But that does not mean that these tissue should not be stretched.

Now is a good time to define what I consider to be a stretch. A stretch is a tensile load. Period.

An elastic material can be under a tensile load and respond with varying amounts of temporary elongation – some materials are stiff and resist deformation, others are compliant and readily deform. When it comes to human connective tissues, it is the load and not the deformation that counts. An applied tensile load triggers a complex cellular process that results in an adaptation. When you stretch a ligament, the cells are signaled to produce more collagen to increase the capacity to withstand the load. When you over-elongate a ligament you end up with reduced capacity to withstand load. Plastic deformation (tissue damage) occurs at 4-8% elongation, causing tearing, inflammation, and eventually scar tissue formation. So stretching connective tissues by applying a tensile load is one thing, but stretching with the goal of making them longer is quite another.

As a yoga teacher, it is important you make this distinction clear. I lie awake at nights worried that there is too much emphasis on elongation and compliance in the yoga community. I’m not kidding. I also lie awake at nights wondering how to convey the message without getting too scientific. Again, not kidding. I continue to lie awake worried about how an easy to understand example or analogy I may give completely distorts the science and how the scientific community will denigrate me. Again, not kidding. Then I cry to my husband/boyfriend who tells me I take myself too seriously and I finally fall asleep while he lies awake worrying about me and all of the above. And before you ask, just be totally clear, the “husband/boyfriend” is one man, not two men. We just haven’t come up with a one word term for what we are.

Let’s get back to creep though and wrap up this blog. I have a sleepless night to get on with.

A recent study on creep in the muscle-tendon unit of actual living humans showed that the steepest slope of the creep curve has been measured to occur within the first 15-20 seconds [2]. After that, elongation continues but at a slowing rate. Since we don’t have any studies on yoga postures and creep, we are left to make educated choices. It is my opinion that if we plan to be in passive stretches for 3-5 minutes, we can reduce the potential of too much elongation by providing proper support.

In the photo above, I have placed a bolster under my head to minimize the creep under the constant load (gravity). The back side of my body is now getting a continuous stretch (tensile load) but is not under continuous elongation. After several minutes in the pose, I can slowly come up and recover.

The moral of the story…use yoga props wisely when holding passive stretches.

When and why you should or should not hold passive stretches is another topic entirely.

__________________________________________________________________________

[1] Svensson, R. B., Hassenkam, T., Hansen, P., & Magnusson, S. P. (2010). Viscoelastic behavior of discrete human collagen fibrils. Journal of the Mechanical Behavior of Biomedical Materials,3(1), 112–115. doi:10.1016/j.jmbbm.2009.01.005

[2] Ryan, E. D., Herda, T. J., Costa, P. B., Walter, A. a, Hoge, K. M., Stout, J. R., & Cramer, J. T. (2010). Viscoelastic creep in the human skeletal muscle-tendon unit. European Journal of Applied Physiology, 108(1), 207–211. doi:10.1007/s00421-009-1284-2

Extend Your Learning: Online Education With Jules

Yoga Biomechanics Livestream

My flagship 3-day livestream course is for teachers who have an insatiable curiosity about human movement and kinesiology, are eager to know what the research says about yoga, and are open to accepting that alignment rules aren’t always accurate. Includes 30 days of access to the livestream replay and slides. 18 CEUs. Learn more >

Your illustration at the end is nice but I can’t say I completely understand the concept you are trying convey. I don’t see how the back side of your body is not continuing to elongate if you are holding the pose. As a yoga instructor, I would appreciate a simplification; regardless of what the scientific community thinks. I’d really like to be able to talk intelligently about why the bolster is a good idea. Although many of my students can’t go far enough in a forward fold to make use of a bolster; assuming I even have bolsters where I’m teaching.

Hi Lisa!

I think you’ve got it. You don’t want the tissue to elongate. You want it to be under a load without an extra elongation. It may help to go back a few blogs. I’ve hyperlinked a few in this blog to some of the past topics. It may help to start with this one here: http://www.julesmitchell.com/tissue-mechanics-connective-tissues/ In simplest terms – stretch your collage fibers past 4% elongation and they become weaker, not longer.

Love this! You always teach me so much Jules. You were spectacular in the use and balance of clinical and informal terms….making it so enjoyable to read. The added info about your personal struggle in educating us and intro to your husband/boyfriend made it even more so! Thank you for your passion and commitment to improving our the way we guide asana.

Thanks Lisa! I appreciate the feedback, always! Love, Jules

Great read Jules. So my question is this….How can we help our students know how to find the place where they need a support? What sensation/sign should they look for to help them know when they are at that point of creep and recovery and not bring themselves past that, possibly injuring tissues? And your comments about how you lie awake wondering how to convey all this, I’m so familiar with that!

That’s such a hard thing to answer, since connective tissues are not equally innervated and everyone translates sensation differently in the brain. But I think a safe rule of thumb is that you should not feel an intense stretch when you’re holding for a long time. It’s really the concept of restorative yoga as we yapana girls know so well. 🙂 I think the concept of pushing past the pain during long held (several minutes) passive stretches is where we get into trouble. Does that help at all?

excellent!

Thank you for this!

Great post! (And yoga-teaching-induced insomnia is the worst!) To Lisa M.’s point, it might be simpler to say that Jules is using the bolster to deliberately limit the stretch to a level that she’s determined is sustainable for her body in that pose. Since she has the bolster there, she won’t sink into it any further from the weight of her head pulling her down, or from the initial loosening up of the tissues that she’s describing. So, the bolster helps her show some restraint in how much she asks of her tissues. As a Yin Yoga teacher who uses lots of props, I notice that people often aren’t aware of how far they’ve stretched until they come out of the pose. Then it’s like “whoa!” So, it’s a good idea to be a little bit on the conservative side (like by using a bolster) so that nothing gets overstretched. And that way, you can give some focus to other aspects of the practice like the breath or cultivating mindfulness, because it’s no longer just about surviving that super intense stretch. You’re totally right that a lot of people can’t fold forward enough to reach a bolster, so you might try having someone like that fold down to a chair seat. Or, if you don’t have chairs, maybe put them in Legs Up the Wall instead. Hope that helps. 🙂

Addie’s comment:

“So, the bolster helps her show some restraint in how much she asks of her tissues.”

This comment is perceptive way beyond its simplicity.

It strikes at the heart of an issue that transcends yoga or any other “fitness” endeavor. It finds its target in the psyche.

If you rent some vehicles they have governors that prevent the vehicle from being driven above a certain speed. Bolsters are governors that prevent the person from exceeding the limit of the plastic deformation threshold of connective tissues. Considering that you can always buy another car or rent another vehicle, but not another body, might be a good idea to bolster your life style and training.

The other key word is “restraint.” Considering the abundance of excess in many people’s thinking, restraint is not very becoming. Restraint has to do in some thinking with “weakness”, “tentativeness”, not going for it, “wimping out” and (god forbid) a lack of flexibility. Restraint is too often implicitly suggestive of a prop for the handicapped and geezers. I mean after all what is going to sell? A photo bomb of someone in 85 asanas without props or 85 asanas with full props? Which winds up on the cover of the yoga rag-azines? Props or nots? And is there not the implicit idea that those who can do the pose without the props in full expression are more advanced than those who succumb to “prop-itis?”

If one of the goals of yoga is to increase mindfulness (adaptability of the psyche) it does not necessarily follow that those who have the most plastic deformable bodies also have corresponding plastic deformable psyches.

Going deeper into the pose is not the goal. Or is it (for some?)

What and why are we asking of our tissues?

Jules, I too have been known to lie awake at night, in my own case, sleepless in Seattle, pondering how to communicate in a thoughtful and intelligent manner the issues you write about. Sometimes I just can’t help it, sometimes I just drift off into the great mysterious and let it go. A good night’s sleep, not agonizing about these issues, is like a good savasana which allows the tissues to rehydrate and fill with fresh fluids. Sleep is savasana for the yogini and a mysterious blessing. Hopefully your husband/boyfriend/ partner/lover/soul mate is not losing too much sleep over all of this. If he is at all gifted in song perhaps he could sing to you those words: “Close your eyes and rest your weary mind. I promise I will stay right here beside you.” I think John had it spot on when he wrote those lyrics. We all write in sand and agonize over trying to get it right and then the tide comes in and washes wisdom as well as mistakes away and the sun surely rises on a new day…….

Those yogis and yoginis whom I dearly love, I refer to your site and we have some of the greatest conversations because of your efforts and our mutual interests. We get a good night’s sleep most of the time knowing that someone somewhere down south is turning the grist for a new day’s blog.. We sleep well knowing that someone else, somewhere is making like the National Guard

Blessing on your blossoms……………..

You may on occasion be sleepless but you are never loveless

Your sleeplessness is greatly appreciated! I toss & turn about these same (t)issues 🙂

I am loving your mission of using scientific research to dispel simplistic yoga-isms. At the same time, as yoga teachers, we’re always brushing up against gray areas, especially when acknowledging that too little or too much tensile load on connective/joint tissues can be a disservice at best, injurious at worst. How we describe and corral our students within an “appropriate range/position” requires the biggest negotiation between our instructions & observations and the students’ self-awareness. But, even when using props, how much “sensation” would you consider to fall within a safe, or beneficial range? Just curious if you have a pre- or post-stretching assessment to determine whether your students have gone too far in loading their joint tissues (aside from “ouch, my knee is killing me”).

Thanks as always for sharing your research!

Well, if you’re going for long holds with support (aka restorative yoga) I would go for minimal sensation of a stretch. The sensation is the contraction of the muscle resisting the stretch – muscles do not relax when stretched, despite what our everyday language suggests. In terms of connective tissue, that’s tougher because it’s less innervated. It’s really a matter of load and deformation which are variable among individuals. In general, if the student can get there actively, that range should be safe. Then use props to manage creep and control the load. Hope that helps!