I am not sure how or why this division came about, but whether or not to bend the knees during a hamstring stretch is a fiercely contested topic in the yoga community. Perhaps it is because injury at the proximal tendon (yellow part of photo below) is quite common among yoga teachers and students. When I lead biomechanics workshops for yoga teachers, I often ask who in the room has experienced, or knows someone who has experienced, proximal hamstring tendon injuries. The show of hands is staggering.

We are keenly aware that something about our practice may be contributing to this mild (and not well documented) epidemic. But our solution is not so keen, “It must be the knee joint angle!”

I have heard teachers argue that a bent knee forward fold is the only way to protect the hamstring tendons from injury. I have heard other teachers argue the opposite, that straight legs is the only way to promote a practice free from tendon tears. Likewise, I have heard both sides argue that their way is the only way to heal an already injured tendon. I have chased these claims for over a decade, looking for data to support the anecdotes, and have yet to come up with anything.

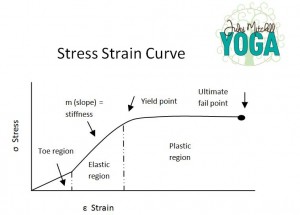

It’s possible that the great yoga debate exists because it is really a matter of biomechanics (load), but is being argued in the language of anatomy (joint position). So let’s put aside anatomy for a moment in order to review some tissue mechanics.

Your hamstring tendons are elastic, meaning they yield under a tensile load/stress (stretch) and return to resting length when the load is removed. Your hamstring tendons have an internal tensile strength, meaning there are limits to the load/stress (stretch) they can withstand.

Tendons also adapt to healthy doses of loading. If you’re new to the blog, pause for a moment here and review my Progressive Overload post. To summarize that post, tendons get stronger with heavy loads and not with light loads.

So how do you load a tendon? With a muscle contraction, of course – as determined by the real estate they occupy (positioned to transmit force between muscle proteins and bone). The muscle contractions associated with passive stretching do not provide a stress great enough to improve the tensile strength of your tendons [1, 2]. This is why I encourage deliberate contractions upwards of 80% of the target muscle, particularly if resistance training is not part of your movement profile.

During hip flexion (forward folding), rather than celebrating one knee joint angle and criticizing the other, I prefer to improve the strength of my muscle contractions in all knee joint angles.

If you’re thinking that a bent knee creates a greater contraction of the lower hamstring fibers, you’re thinking of concentric contractions and forgetting that muscles produce force at varying lengths. Sometimes even greater forces after a stretch! Here’s a past blog on how muscles actually work [3].

I only bring up the contraction conversation here because we recently wrapped my 300 hour teacher training and we probably reviewed this subject every single day, some days even twice per day! One of my major themes was to encourage the teachers to think beyond concentric contractions and to take a bird’s eye view, instead of a literal view, of the anatomy book. And this meant climbing on my soap box over and over and over again.

But I didn’t mind. In fact, I was grateful. Those teachers really showed me which topics are needed in yoga teacher trainings and biomechanics is a clear winner.

Back to the knee joint angle during hip flexion…

One of the best ways, in my opinion, to evaluate stretch positions is to look at the orthopedic testing procedures, since most sports rehab professionals use methods of treating and training that mimic testing methods. You won’t be surprised to learn that there are three common positions used for testing hamstring tightness extensibility – one bent knee and two straight knee positions.

When determining which test to use, researchers consider the merits of these tests. They consider factors such as reliability and validity [4, 5, 6]. Protecting the hamstrings tendons from injury based on knee joint angle is not a consideration because hamstring tendon strength is not dependent on knee joint angle. Hamstring tendon strength is dependent on the loading history of those tissues.

Researchers do, however, consider that in some individuals, the Straight Leg Raise (SLR) test, which looks an awful lot like a straight leg supta padangusthasana, may stretch neurological tissue and thus interfere with the ability for the hamstrings to yield [4]. In this case, the Active Knee Extension (AKE) test, where the hip is flexed and fixed to 90° in a supine position while the subject tries to actively extend her knee, is preferable over the SLR. (This stretch can also be performed passively with assistance, photo below left.) The third test, the Sit and Reach (SR) which resembles paschimottanasana, is generally considered the least reliable and valid for obvious compensatory contributions of the spine (photo below right). Researchers defend superiority of these tests in terms of effectiveness (reliability and validity) based on data rather than oral traditions.

(images by Shutterstock)

Regarding effectiveness measured by improvement in flexibility, researchers utilize bent knee stretches [7, 8, 9, 10], straight knee stretches [11], or both [12, 13]. Clearly, if one of these methods were considered injurious, it would not be approved for testing on human subjects.

As leaders and educators in the yoga community, we can advance conversation beyond debating the merits and consequences of bent or straight leg forward folds* (anatomy) by including the promotion of connective tissue health (biomechanics). Basically the topic of my last post.

*This post discusses the effect of forward folds on the hamstring tendons, not vertebral discs or any other structures which would require an entirely different post.

______________________________________________________________________

[1] Kubo, K., Kanehisa, H., & Fukunaga, T. (2002). Effect of stretching training on the viscoelastic properties of human tendon structures in vivo. Journal of Applied Physiology, 92(2), 595–601. http://doi.org/10.1152/japplphysiol.00658.2001

[2] Kubo, K., Kanehisa, H., Miyatani, M., Tachi, M., & Fukunaga, T. (2003). Effect of low-load resistance training on the tendon properties in middle-aged and elderly women. Acta Physiologica Scandinavica, 178(1), 25–32. http://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01097.x

[3] Minozzo, F., & Lira, C. (2013). Muscle residual force enhancement: a brief review. Clinics, 68(2), 269–274. http://doi.org/10.6061/clinics/2013(02)R01

[4] Gajdosik, R., & Lusin, G. (1983). Hamstring muscle tightness. Reliability of an active-knee-extension test. Physical Therapy, 63(7), 1085–1090.

[5] Hamid, M., Ali, M., & Yusof, A. (2013). Interrater and Intrarater Reliability of the Active Knee Extension (AKE) Test among Healthy Adults. Journal of Physical Therapy Science, 25(8), 957–61. http://doi.org/10.1589/jpts.25.957

[6] Kane, Y., & Bernasconi, J. (1992). Analysis of a modified active knee extension test. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 15(3), 141–146.

[7] Davis, D., Ashby, P. E., Mccale, K. L., Mcquain, J. A., & Wine, J. (2005). The effectiveness of 3 stretching techniques on hamstring flexibility using consistent stretching parameters. Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, 19(1), 27–32.

[8] Freitas, S. R., Vilarinho, D., Vaz, J. R., Bruno, P. M., Costa, P. B., & Mil-Homens, P. (2014). Responses to static stretching are dependent on stretch intensity and duration. Clinical Physiology and Functional Imaging. http://doi.org/10.1111/cpf.12186

[9] Magnusson, S. P., Simonsen, E. B., Aagaard, P., Gleim, G. W., McHugh, M. P., & Kjaer, M. (1995). Viscoelastic response to repeated static stretching in the human hamstring muscle. Scandinavian Journal of Medicine & Science in Sports, 5(6), 342–347.

[10] Magnusson, S. P., Simonsen, E. B., Aagaard, P., & Kjaer, M. (1996). Biomechanical Responses to Repeated Stretches in Human Hamstring Muscle in Vivo. The American Journal of Sports Medicine, 24(5), 622–628.

[11] Borman, N. P., Trudelle-Jackson, E., & Smith, S. S. (2011). Effect of stretch positions on hamstring muscle length, lumbar flexion range of motion, and lumbar curvature in healthy adults. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 27(2), 146–154. http://doi.org/10.3109/09593981003703030

[12] Fasen, J., O’Connor, A., Schwartz, S., Watson, J., Plastaras, C., Garvan, C., … Akuthota, V. (2009). A randomized controlled trial of hamstring stretching: comparison of four techniques. The Journal of Strength & Conditioning Research, 23(2), 660–667.

[13] Meroni, R., Cerri, C. G., Lanzarini, C., Barindelli, G., Morte, G. Della, Gessaga, V., … De Vito, G. (2010). Comparison of active stretching technique and static stretching technique on hamstring flexibility. Clinical Journal of Sport Medicine, 20(1), 8–14. http://doi.org/10.1097/JSM.0b013e3181c96722

Extend Your Learning: Advanced Yoga Teacher Training with Jules Mitchell

This program is ideal if you have an interest in biomechanics, principles of exercise science, applications of pain science, neurophysiology, and stretching. These themes are combined with somatics, motor control theory, pose analysis and purpose, use of props for specific adaptations, pathology, restorative yoga, and intentional sequencing.

You will learn to read original research papers and analyze them for both their strengths and their biases. Critical thinking and intellectual discourse are central components in this training, which was designed to help teachers like you navigate through contradictory perspectives and empower you with education. Learn more >

Thanks Jules, as a former research librarian, I appreciate how you support your writing with references to peer reviewed research. And when is that other post coming, the one on “the effect of forward folds on vertebral discs?” That’s a debate on see a lot and would value your insight.

Okay, I think I understand that a bent knee doesn’t prevent injury to hamstring tendons and an unbent knee doesn’t necessarily create injury. So where are all the tendon injuries coming from? Am I correct in concluding that you are saying straight-leg forward folds do NOT create hamstring tendon issues? As a yoga teacher, once a student has told me that they have a hamstring tendon injury, what do I do to help them heal and/or avoid further injury? I know nothing is as simple as it seems, but it you can provide a few universal principles to keep in mind regarding hamstring tendon preservation, I would be extremely grateful! By the way, I love how you are melding science with the art of yoga – many thanks!

Hi Susan,

One word: Load

“So how do you load a tendon? With a muscle contraction, of course – as determined by the real estate they occupy (positioned to transmit force between muscle proteins and bone). The muscle contractions associated with passive stretching do not provide a stress great enough to improve the tensile strength of your tendons [1, 2]. This is why I encourage deliberate contractions upwards of 80% of the target muscle, particularly if resistance training is not part of your movement profile.”

Hope that helps!

Love,

Jules

Michele,

That other post will come one day. You know how long it takes to write one of these and I’m currently teaching 6 days a week! One day. Thanks for reading, as always.

Love,

Jules

As I read your article, the same concerns and questions come up…same as the ones brilliantly addressed by Michele and Susan. This article, to me, misses the most important aspect to take care of – the spine! Thus, this article can mislead many when safety parameters are not clear.

Even when the legs are straight in a forward folds, if the natural curvature of spine is lost what and where one is stretching becomes an even bigger debate.

Yup. Agreed. That’s a whole different topic though and a much much much longer blog. But I will tell you, there is no one answer there either. It will depend on the student, the loading history, the posture, the desired outcome, etc. etc.

Thanks for reading and commenting!

While the posterior thigh tissue is lengthened on a forward bend, are you familiar with Andre Vleeming’s research (2008) into straight leg raises and facial strain? He found, for instance, that IT band is stretched 240% relative to the posterior thigh.

Yes, as well as strain on contralateral structures. Interesting stuff.

Interesting stuff…thanks as always for sharing it. One thought that you may not be fully accounting for given the research you cite: ignoring for a moment the SR test (which, let’s be honest, nobody really likes or uses outside grade school gym class), all the research you reference (regarding both SLR and AKE) seems to focus only on open chain actions.

But a standing forward fold like the one you drew is a closed chain action. I can imagine that the loading pattern could be quite a bit different in that particular exercise, and the research here somewhat less relevant. Speaking purely from personal experience with a proximal hamstring tendon injury, I swear I could feel a significant (and beneficial) loading difference with bent knees in a standing fold. And perhaps coincidentally, it’s in these standing folds I usually hear the bent-knee cueing. I’m totally open (and interested) in the possibility that I was compensating in other ways to make that difference.

But more to the point of your excellent post, and again speaking purely from personal experience, gradual increasing the eccentric loading on that hamstring was ab.so.lutely vital to my healing process. Thanks for the post. Keep ’em coming.

Just an observation: since everything in the body is related and interconnected in the field of biomechanics and loads I would recommend reading “low back disorders” Evidence-based prevention and rehabilitation, by Stuart McGill second edition .

Jules, when you were in Flagstaff, you mentioned you’d be chatting with “the yin guys” to get a more accurate sense of what yin is really about before commenting too much about it. Has this happened yet? I’m curious, because my limited personal experience (from past class attendance) is that it’s the whole “let go” approach…but not in “fully supported, 100% supported restorative yoga, where you aren’t feeling that stretching sensation we are all addicted to.” I’ve been introducing RESTORATIVE postures into classes, which even lead to folks asking for an all restorative class. They really like it, but people are also asking for yin specifically. There’s just something about it people seem to like/crave – a sense of intensity perhaps – maybe its the addiction to that stretching sensation you mentioned. I’m not sure. As of now, I’m really only comfortable offering passive stretches (held for >1minute) that are fully supported. Otherwise, I feel these held postures might be better practiced with isometric engagement (like the way you demo malasana with a blanket or eggs under the heels)…but then it’s no longer yin. Love to read/hear your insight related to yin.

Oh and I didn’t think to emphasize in my above comment that I didn’t actually expect a direct reply, especially not condensed to a comment. More along the lines of thinking it’d make for an interesting topic for blog or social media after you attend the fascia conference. I posted here in an attempt to avoid over emailing you. Oops.

Haha, no worries. I have a whole list of comments I need to answer. They are just sitting at the bottom of a long list of correspondence items. I always welcome your comments. Thanks Allie!