Clarifying the Confusion Around “Engaging” A Muscle While Stretching It: A Guide for Yoga Teachers

Are you the type of yoga teacher who loves to promote active stretching and muscle engagement during your classes? You might say things like “hug the muscle to the bone” or “engage the hamstrings” in a forward fold.

I’m with you. I really like this type of stretching. You might call it active stretching, but it’s more specifically an isometric stretch. Unfortunately, I often hear it referred to as an eccentric. And not just in classes or on social media. In my own 300 hour yoga teacher training, the participants get this one wrong on their homework all the time!

I thought I’d share a short video demonstration and a bit of education around this topic. I hope it helps!

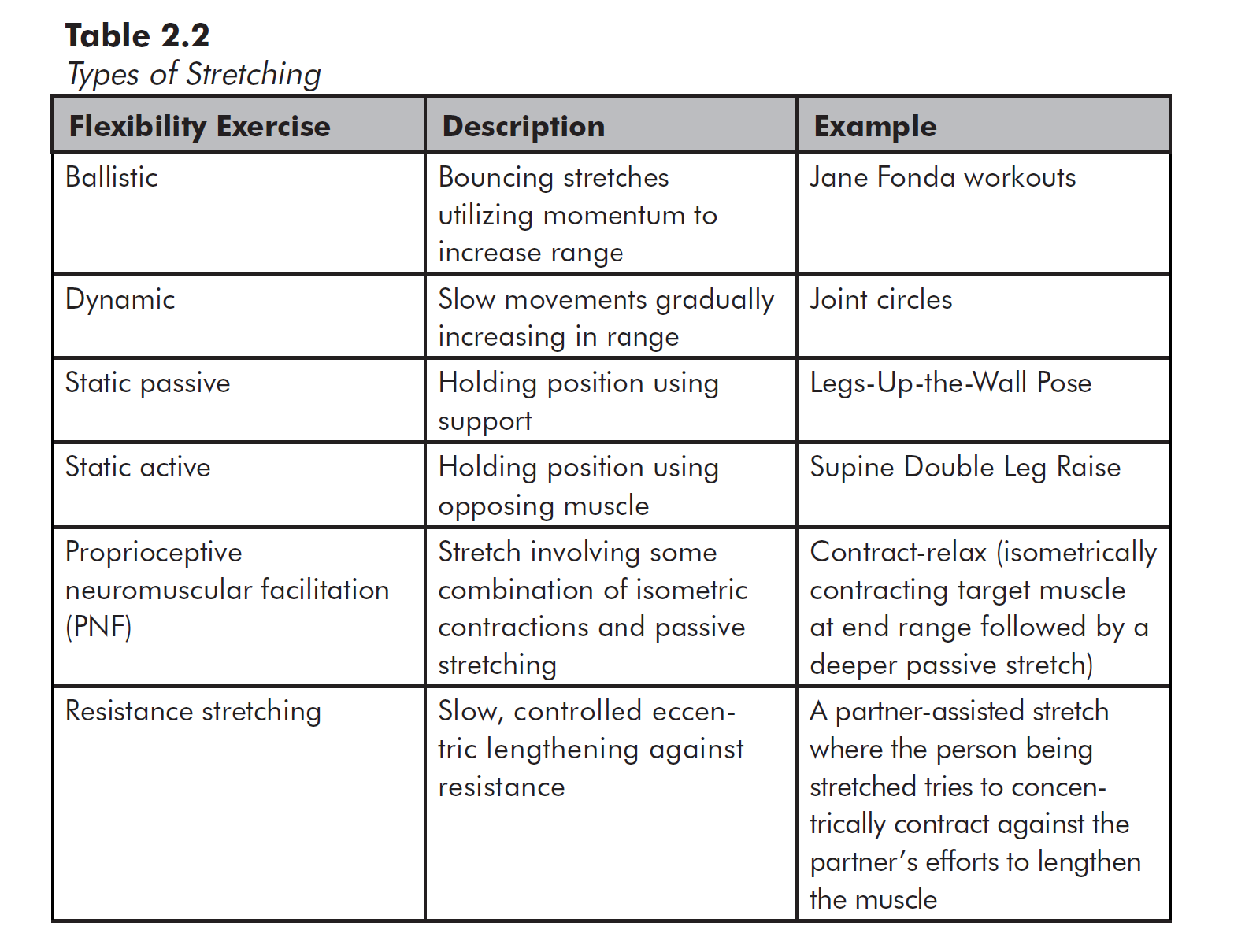

But first, let’s briefly review the 6 types of stretching.

The 6 Types of Stretches

Depending on the authority, you’ll learn somewhere between 4 and 6 types of stretches. Personally, I like to categorize them into 6 different types because you perform they employ 6 different techniques. Here is my list:

- Ballistic

- Dynamic

- Static Passive

- Static Active

- PNF (or what I like to call Isometric Stretching)

- Resistance Stretching (or Eccentric Stretching)

You can learn a little more about these in the table from my book I posted below. In this blog I will discuss the difference between the last 2 categories of stretching because this where I see yoga teachers get easily confused.

Isometric vs Eccentric Stretching

Eccentric stretches have 2 main requirements:

- You have to be moving. If you’re holding a stretch it’s a passive stretch. If you’re holding the stretch but actively pressing in the opposite direction into an immovable object/surface, it’s isometric (for the target muscle).

- You have to be actively trying to move in the opposite direction, while you’re being lengthened by some external force. If you engage a muscle in a lengthened position, but the target joint angle isn’t changing it doesn’t qualify as eccentric.

The example I give in the video below confuses a lot of yoga teachers. I get it, there’s no real easy way to move the leg. I could put my heel on a cartoon banana peel 🍌 and decelerate the lengthening. Or, I could reduce the hip joint angle by hinging more at the hips (while maintaining the deliberate heel drive!), thus gravity combined with the weight of my trunk and head being the external load.

The key eccentric stretching takeaways are:

- If you’re not moving it can’t be eccentric.

- Just because you engage a muscle in a lengthened position, if it’s not actively lengthening (i.e. the joint angle isn’t changing), it can’t be eccentric.

- If you are moving, for it to be eccentric, you have to be actively trying to move against the direction of movement.

This is where biomechanics becomes an important education tool for yoga teachers. I spend most of my online and in-person weekend courses going over force vectors, muscle contraction types, levers, gravity, and yoga props as objects of resistance. It’s a ton of fun. I hope you join me some time!

What did you learn? Was this obvious to you or did it clarify a few differences for you? Are there other poses you have questions about? Comment below and I’ll be sure to answer.

Extend Your Learning:

Online Education With Jules

The Science of Stretching Webinar 5.0

This webinar is for teachers and students who have an insatiable curiosity about stretching, what it does, and how it works, while accepting that conventional stretching wisdom isn’t always accurate. Eligible for 3 CEUs. This course is offered in January and July each year. Learn more >