This post is another Thought Provoker inspired by the dissection course I led last month, this time focusing on the lumbar spine.

Anatomy Labs for Yoga Teachers

One of the reasons I return to the lab year after year is that no two labs are the same. While the curriculum might be the same, variability of human anatomy ensures that no dissection course will ever be the same. Additionally, the variability of the group dynamic further ensures a new experience every time. The specific dissections, the conversations, and the interests of each group are totally unique. The lessons that come out of each course are influenced by both the anatomy of the cadaver and the collective contributions of the participants.

Lumbar Discs, Spinal Flexion, and Adaptability

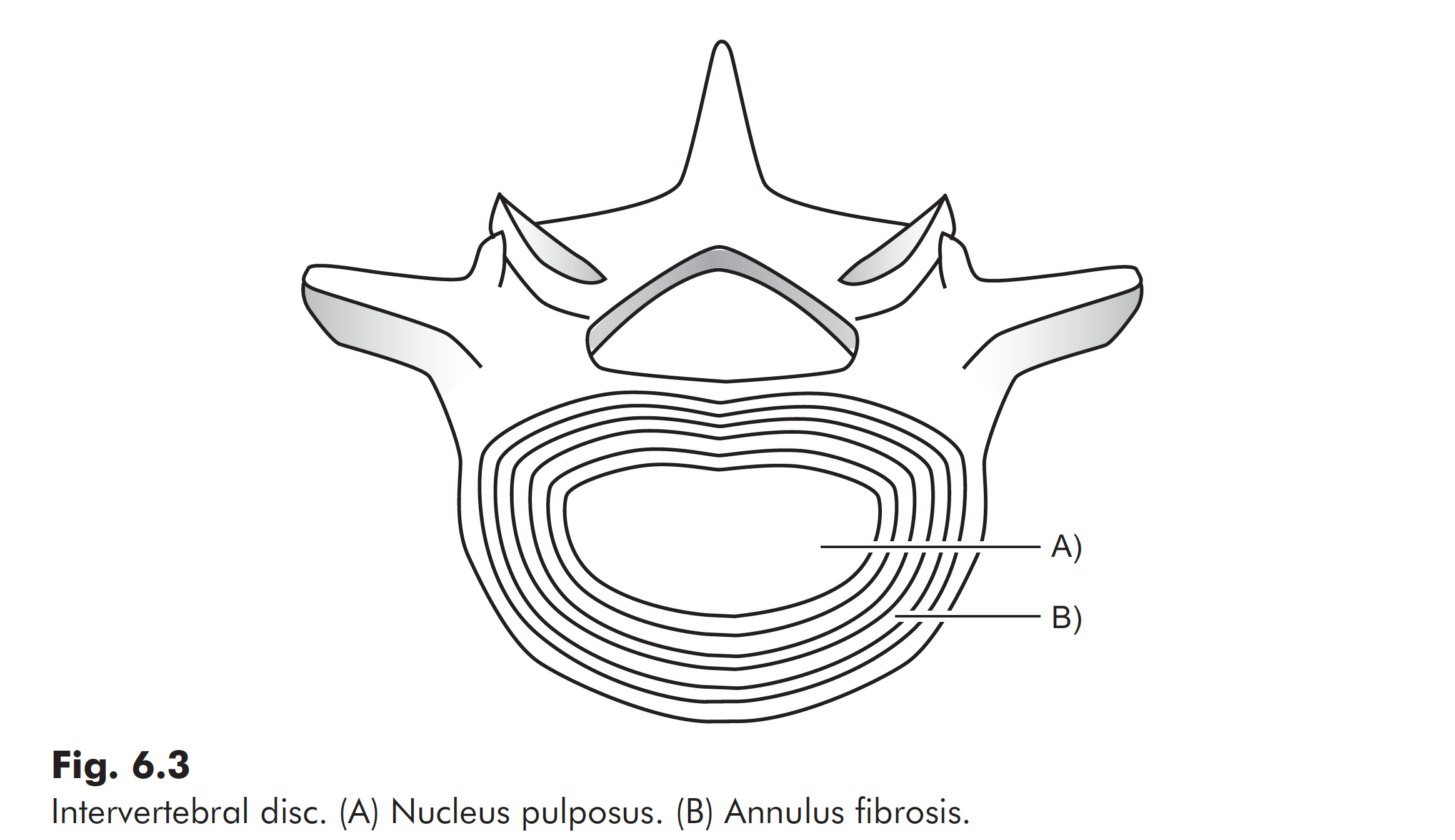

One of the big insights that I heard around the tables in this most recent lab was the enormity and density of the lumbar vertebral bodies and discs. Apparently, some of the participants expected something a lot more delicate. Another was the densely packed fibrous collagen rings that make up the disc, resembling tree rings and invoking an image of growth and strength that builds over time. Even though we’re told discs are made of fibrocartilage, it isn’t always apparent that means collagen – the highly stable protein that can be stressed to great degrees, for long periods of time without compromising its resting tension. One participant expressed in response to the lumbar spine: “The human body is so much more than you think it is, or what you’ve been told it is.“

I wrote in my last post “notorious structures (think the “loose” SI joint, the chronically “tight” IT band, the “fragile” knee ligaments, the flexion “intolerant” lumbar spine, etc.) are elusively described in the classroom and poorly depicted in the textbooks. When one has the opportunity to locate, identify, touch, and dissect these structures, the narrative changes quite quickly.” This is exactly what happened regarding the lumbar spine.

We rewrote stories, reframed experiences, and reconstructed the model, all against the backdrop of the research cited in my book and in conjunction with what we observed.

In today’s post, I share with you an image from my book, Yoga Biomechanics: Stretching Redefined, along with an excerpt from the related text, followed by two Thought Provokers. While these aren’t formal “Thought Provokers” you’ll find in the sidebar of the book, I’m offering them to you here so you can ponder them for yourself. If you teach anatomy, they make great topics for group discussions. As always, feel free to comment with your musings. I will reply.

Excerpt from Spinal Flexion

(Chapter 6: pgs 170-171)

While we cannot say with any certainty the impact a yoga class might have on lumbar discs, we can look briefly at the research on disc properties. In the context of tissue adaptation, IVDs have classically been thought to be mostly inert. Much like articular cartilage, the fibrocartilage discs possess an ECM structure that impedes turnover and regeneration. Research today might be suggesting otherwise. First, herniated discs are now known to have the ability to spontaneously regress without surgical interventions (Chiu et al., 2015; Zhong et al., 2017). This raises questions about the finality of disc herniations, and when combined with the asymptomatic cases, everything becomes even more uncertain. Second, the famous Twin Spine Study found genetic factors to be a determinant for disc degeneration but loading associated with daily physical activities did not appear to cause wear (Battié et al., 2009). Third, we understand that certain loading conditions promote a structure and composition which might promote disc health (Steele et al., 2015). Two such loading conditions found to increase disc hydration include running (Belavý et al., 2017) and, unexpectedly, slouched sitting (Pape et al., 2018). None of these perspectives are intended to promote spinal flexion with reckless abandon; they are insightful inquiries to the larger question of how we can increase capacity while maintaining safety with the practice of yoga.

Explore These 2 Thought Provokers Relating to the Knee

Use these questions to challenge yourself, expand your comfort zone, and stimulate new insights.

Thought Provoker #1:

What is your understanding of the adaptability of spinal discs? How do your students generally view the lower back on a scale from fragile to resilient? Does this perception change when there is pain? What image does the rubber disc or the red “bulging disc” in the classroom skeletal models conjure? How has this translated to the way cue certain poses like backends or forward bends? Does your language support or contradict the prevailing narrative around lumbar flexion? Are certain yoga poses protective for the lumbar or should the lumbar be protected from certain yoga poses?

Thought Provoker #2:

Do you emphasize a straight (or neutral) spine in seated poses, forward bends, or twists? Do you explain why you do or do not? How attached are you to your explanation? What image does the plastic skeletal model of a spine conjure? What structures are missing from the front, back, and inside of that model? Could these structures play a role in perceptions, movement, or even force transmission even if they aren’t musculoskeletal tissues? What is the role of water, elastin, or ground substance in disc health? How does chemistry relate to biomechanics and does it shed light on what beliefs certain biomechanical models reinforce?

Extend Your Learning:

Online Education With Jules

The Science of Stretching Webinar 5.0

This webinar is for teachers and students who have an insatiable curiosity about stretching, what it does, and how it works, while accepting that conventional stretching wisdom isn’t always accurate. Eligible for 3 CEUs. This course is offered in January and July each year. Learn more >