It’s been a while since I’ve blogged. I have been teaching all over North America and between traveling, updating my slideshow, creating handouts, seeing private clients, and making time for a personal yoga practice, writing time has been scarce.

Then we had this election. I have no interest in getting political on my blog. But I will say that two things have viscerally troubled me:

- The lack of respect when communicating with the other side is only making things worse. Conflict resolution does not rise out of attacking, insulting, or blocking.

- The lack of consideration given data shared. Just because it’s in print, doesn’t make it true, correct, right, or valid.

So I was lamenting with some colleagues about how I am feeling conflicted about teaching and writing at this time. Don’t we have more pressing concerns than a nagging, albeit tolerable, pain below the butt during yoga class? I mean really, let’s get some perspective here.

But then I was served perspective by my friend and colleague Catherine Cowey. She reminded me that our work is also about scientific literacy and critical thinking skills. And that by questioning things we’ve been taught about asana on our mats, examining the available evidence, and then choosing the best course of action, we learn to evaluate what we see, what we read, and what we hear.

And so I started writing.

Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy

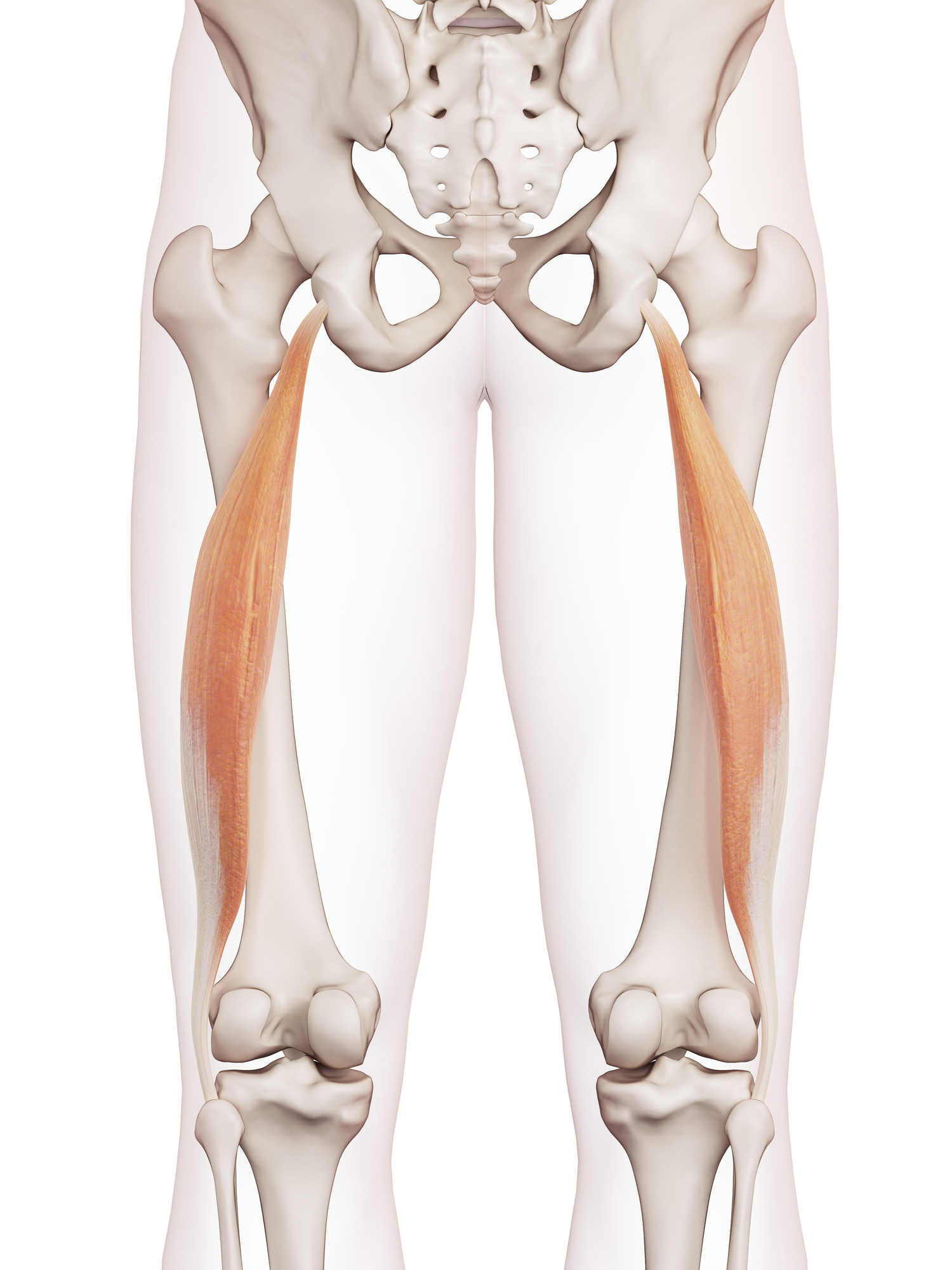

Proximal means closer to the trunk, thus referring to the tendinous attachment of the hamstrings at the sitting bones on the ischial tuberosity.

Long head of the biceps femoris

(image by Dreamstime)

Tendinopathy means a pathological tendon presenting with pain and dysfunction [1].

Back when I was in school, we learned that the term tendinopathy evolved by merging two conditions – tendonitis and tendinosis. An –itis refers to inflammatory conditions where an –osis refers to degradation. But since a chronic inflammatory environment provokes degradation and vice versa, these two conditions often occur simultaneously [2]. In this scenario, neither -itis nor an –osis accurately describe the syndrome, hence the use of –opathy.

Today, the tendon research is more robust, specific, and multi-disciplinary. So is the pain research. We now understand how poor the correlation is between tissue damage and pain. An MRI report, a postural/mobility “defect,” or a flexibility limitation cannot predict an individual’s pain [3]. Because the term tendinopathy includes painful tendons (even in the absence of a histological examination), the term encompasses a vast array of pathologies, defined broadly by the presence of pain and dysfunction.

Scope of Practice

For yoga teachers, broad descriptors are useful. Since most of us don’t hold medical licenses, we don’t diagnose or treat. But we do work with people who suffer from common ailments, including proximal hamstring tendinopathies. People come to us either when they experience everyday aches and pains that are not complex enough to require medical intervention. They also come to us when they’ve completed their medical treatment or physical therapy and have been given the green light to resume activities (such as yoga).

Understanding what a proximal hamstring tendinopathy is and how it resolves will make you a more confident and effective yoga teacher.

Not only will you help people with tendinopathies; you will also help people prevent them. The rehab model translates very well to the training model and vice versa. So while you may not rehab students (because it is out of your scope), you prehab (train) them. And the number one thing you can do is get those hamstrings stronger (which is entirely in your scope).

What to Do

The usual advice for PHT I see, hear, and read in the yoga world includes:

- Stretch it out

- Bend your knees when you forward fold

- Straighten your knees when you forward fold

I wrote about proximal hamstring tendinopathy once before in the context of whether or not your should bend your knees in forward bend. The message was clear: get stronger because neither is incorrect. I’ll discuss in more detail today.

While there isn’t much research on PHT and even less on yoga, we can learn from Achille’s tendon and patellar tendon research. We can also learn from the pain research and the sports science research. And he is what we know: tendons respond favorably to tension, but compression may negatively affect the internal structure [4].

Muscle contractions deliver tensile forces to the tendon. It is the job of the tendon to transmit muscle force to bone. Tendons adapt to become stronger in the presence of muscle contractions, just as bones adapt to become stronger in the presence of weight bearing exercises (favorable responses).

Muscle contractions need to be strong enough to elicit adaptation, however. 70% maximum voluntary contractions (MVC) to be specific [5]. Passive stretching in which you are instructed to relax your muscles is not enough. You can’t passively stretch your way to tendon strength (or any connective tissue strength for that matter).

Here is where yoga teachers confuse force (stress or load) with stretch (strain or deformation). Tendons don’t need to be stretched; they need to be loaded (yes, it happens to stretch them, but it’s not the same thing). I must save this distinction for another blog, or I’ll lose sight of this one. But if you’ve read through my blogs or taken one of my courses, this should make sense to you.

PHT and Yoga

The single most etiological (causative) factor for PHT in tendons is currently believed to be compression [6]. Compressing the tendon can happen by simply sitting too long on your sitting bones. Or it can happen through prolonged stretches in the position of hip flexion. When you flex your hip deeply, the hamstring tendon gets stretched over the ischial tuberosity (I demonstrate this with a theraband and a skeleton in a live course and at cocktail parties) which compresses the tendon over that boney protuberance. The greater the flexion, the greater the compression.

Think of all the yoga poses that compress the hamstring tendon through hip flexion: Downward facing dog. Lunges. Warriors (all of them). The Triangles. Pyramid. Dve (the hip hinge in a Sun Salutation). Hanumanasana. Any seated forward fold. I’ll let you finish the list.

(image by Dreamstime)

(image by Dreamstime)

Before you get defensive, I’m not saying these poses are bad or that hip flexion is bad. Or that sitting is bad. Or even that these poses cause PHT. I’m looking at yoga through a research lens and evaluating the best course of action for a student who has mentioned that nagging but tolerable pain and wants it to go away.

If compression aggravates the symptoms, then the first thing to do is limit flexion. Not forever, but temporarily. Some suggestions:

- Blocks in standing forward folds

- Maybe a little less hip hinging for awhile

- Probably hold off on Warrior 3

You get the idea.

For some people, simply keeping the legs straight in a forward fold will take them out of the hip hinge because of “tight” hamstrings. But not everyone!

Isometrics

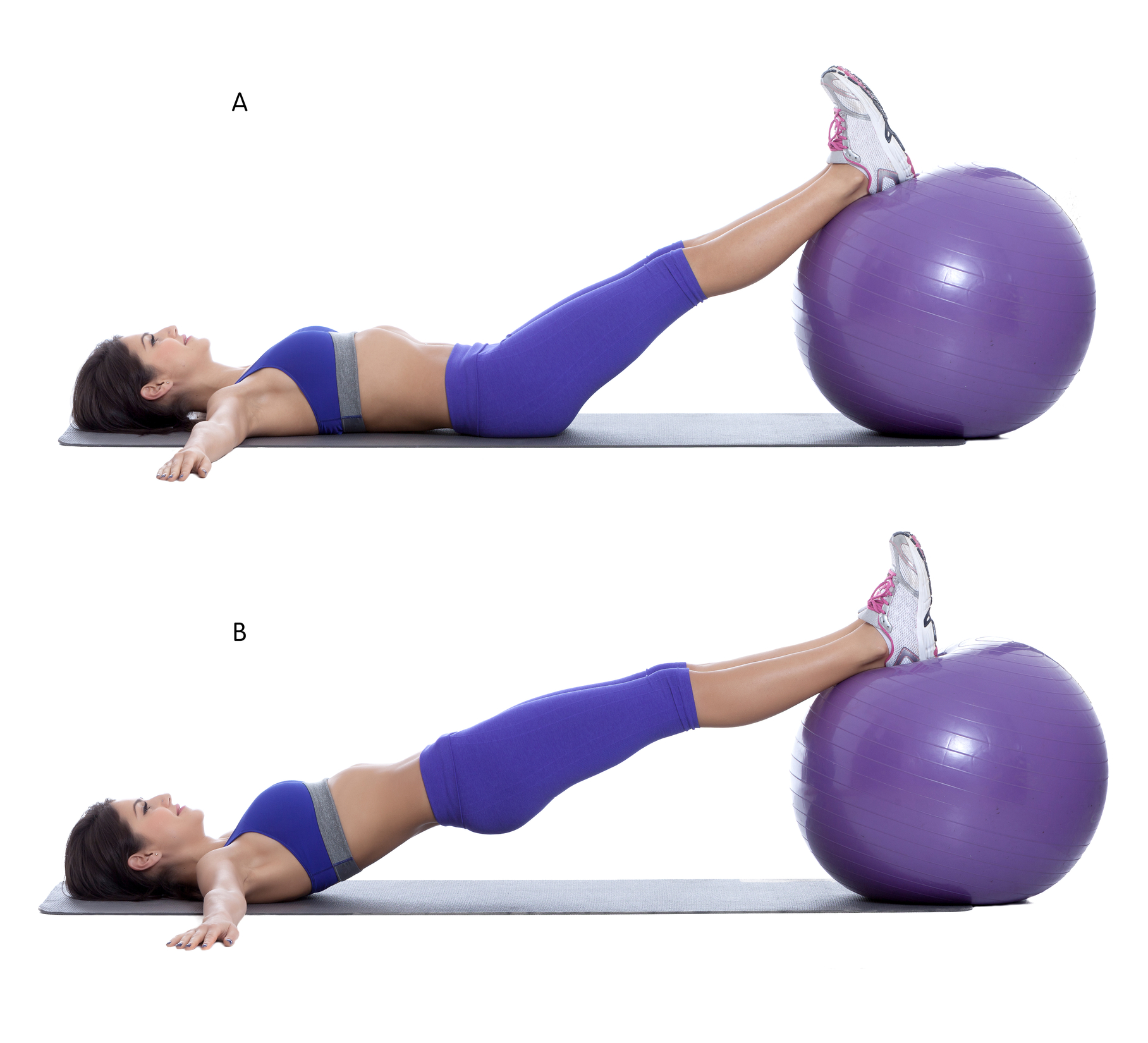

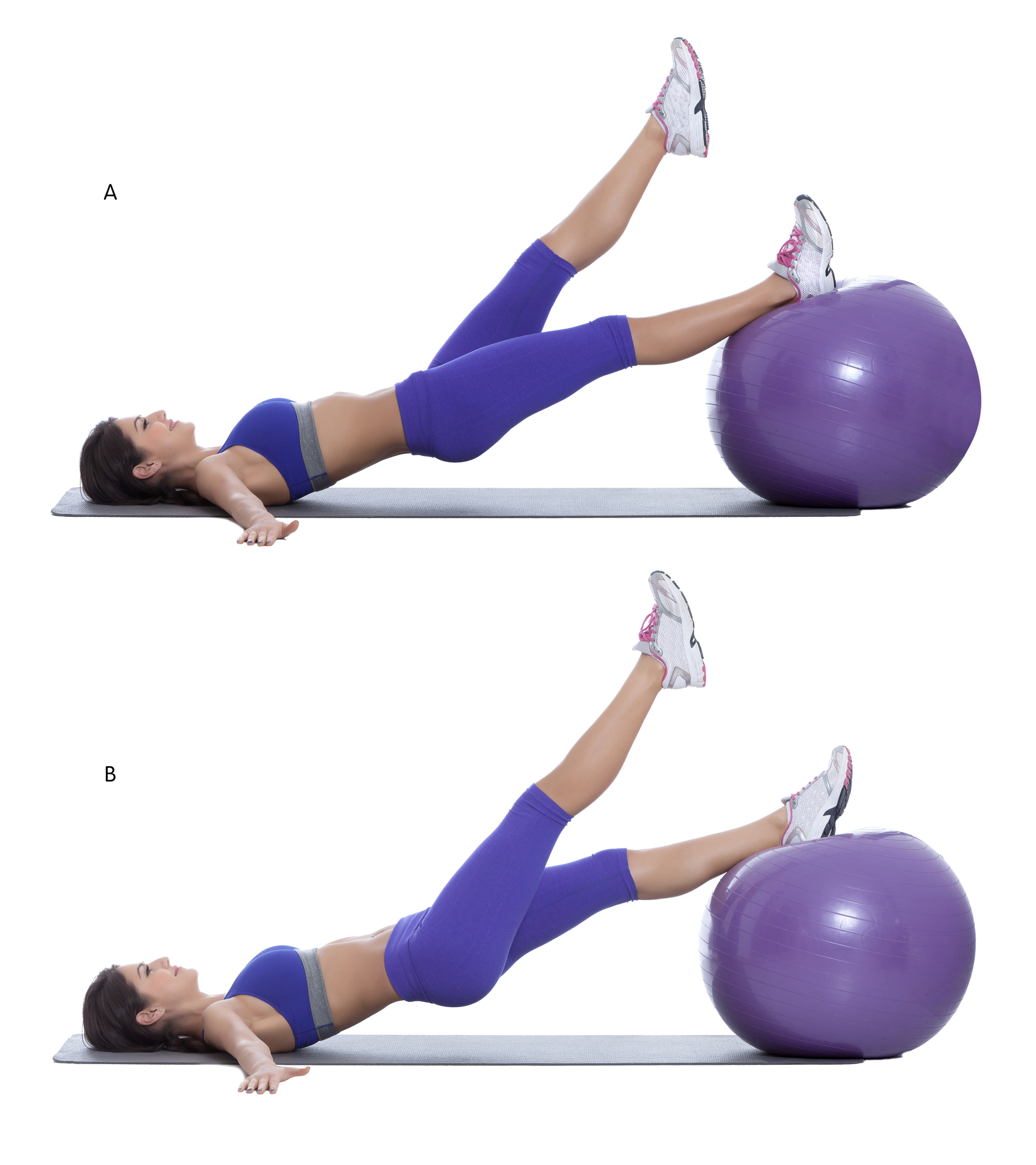

In conjunction with limiting hip flexion, strengthening the hamstrings (to get those tendons more resilient) is a wise choice because avoiding postures that recreate symptoms won’t increase the capacity to tolerate the postures when returning to them in the future. Some suggestions (in order of progression):

(images by Dreamstime)

(images by Dreamstime)

You don’t have to use an exercise ball – these were all I could find in the stock image library. A yoga chair, blocks, bolsters, or the wall will work just fine. A regular yoga bridge (with the glutes and hamstrings engaged!) will also work, progressing it by taking the feet further away from the pelvis (yes, not proper yoga alignment but that’s okay and also a topic for a future blog) and adding single leg options.

These are all isometric holds – which is what we do in yoga anyway! Isometrics are good for both strengthening and are known to induce analgesia (reduce pain). 45-second isometric holds for 5 sets at 70% MVC has been successful in reducing painful symptoms in the patellar tendon [1].

Isometric holds can then progress to isotonic loads. For example, you can bridge with your feet on a yoga blanket or a small towel and slowly slide the feet away from the pelvis and back in. Eventually, you’ll introduce poses that require greater degrees of hip flexion (progressively, of course). At some point, it would probably be prudent to progress beyond body weight exercises as well, but this is a yoga blog, so I won’t say much more about that now.

How Long Does it Take?

The biggest challenge I find in working with tendinopathies is the timeline. It would be much easier if all people presented identical symptoms and responded to each yoga pose in exactly the same way. But they don’t. The best advice I have to offer is to be diligent and patient. Connective tissues take time to adapt (sometimes up to 2-3 years!). The timeline for pain is even more complicated. So do your best to avoid aggravating the area and stay on top of those isometrics.

How This Applies to Teaching

If you teach group classes and have students dealing with PHT-like symptoms, overwhelm them with permission to avoid deep hip flexion postures, for now. Offer them bridge instead of the seated forward folds we generally offer at the end of class. Remind them that if they feel better in 2 or 3 days, it’s likely an analgesic response to the yoga practice, and doesn’t indicate they are ready for a full range of motion practice. Tell them they can’t go wrong getting strong.

More importantly, apply this information to how you teach yoga. Remember, yoga teachers don’t diagnose or treat. But they do teach yoga. You have choices on how you sequence your classes, which poses you teach, how long you hold them, and the cues you give. If you understand how tendons adapt to load, you can do your part to help reduce the instances of nagging upper hamstring pain in the yoga-sphere.

In the spirit of scientific literacy, I hope you evaluate and question everything I wrote above (please not by attacking, insulting, or blocking) and consider before sharing (but please do share if you find this information useful).

_________________________

[1] Rio, E., Moseley, L., Purdam, C., Samiric, T., Kidgell, D., Pearce, A. J., … Cook, J. (2014). The pain of tendinopathy: Physiological or pathophysiological? Sports Medicine, 44(1), 9–23. http://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0096-z

[2] Abate, M., Silbernagel, K. G., Siljeholm, C., Di Iorio, A., De Amicis, D., Salini, V., … Paganelli, R. (2009). Pathogenesis of tendinopathies: inflammation or degeneration? Arthritis Research & Therapy, 11(3), 235. http://doi.org/10.1186/ar2723

[3] Lederman, E. (2011). The fall of the postural-structural-biomechanical model in manual and physical therapies: Exemplified by lower back pain. Journal of Bodywork and Movement Therapies, 15(2), 131–138. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbmt.2011.01.011

[4] Docking, S., Samiric, T., Scase, E., Purdam, C., & Cook, J. (2013). Relationship between compressive loading and ECM changes in tendons. Muscles, Ligaments and Tendons Journal, 3(1), 7–11. http://doi.org/10.11138/mltj/2013.3.1.007

[5] Bohm, S., Mersmann, F., & Arampatzis, A. (2015). Human tendon adaptation in response to mechanical loading: a systematic review and meta-analysis of exercise intervention studies on healthy adults. Sports Medicine – Open, 1(1), 7. http://doi.org/10.1186/s40798-015-0009-9

[6] Goom, T. S. H., Malliaras, P., Reiman, M. P., & Purdam, C. R. (2016). Proximal Hamstring Tendinopathy: Clinical Aspects of Assessment and Management. The Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy, 46(6), 483–493. http://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2016.5986

Extend Your Learning: Advanced Yoga Teacher Training with Jules Mitchell

This program is ideal if you have an interest in biomechanics, principles of exercise science, applications of pain science, neurophysiology, and stretching. These themes are combined with somatics, motor control theory, pose analysis and purpose, use of props for specific adaptations, pathology, restorative yoga, and intentional sequencing.

You will learn to read original research papers and analyze them for both their strengths and their biases. Critical thinking and intellectual discourse are central components in this training, which was designed to help teachers like you navigate through contradictory perspectives and empower you with education. Learn more >

Thank you! Splendidly lucid, & very useful. Thank you for al your work!

Thank you so much for this post. I have often wondered about that “nagging but tolerable pain” and the proper way to resolve it. This was illuminating.

Wish I’d read this blog 5 years ago!

Took me a good while to work out what was causing that ” tolerable but nagging pain” (ie. forward bends in a range of asanas; not just the obvious ones like IUttanasana or Pascimottanasana) then what to do. I think 2-3 years of backing off the degree of hip flexion and starting one on one weight work once/week keep it in check. Now it’s vigilance in hip flexion asanas and playing the edge with how much flexion is ok today. A work in progress!!

Thanks Jules. As always, great information and very helpful. Look forward to more writing…

I didn’t know what had been bothering me for two years…when I found your forward bend knees straight or bent post, I knew. Thank you so much for writing this. And I’ll see you in Omaha in January!