Don’t you just love it when worlds collide? I have been friends with a #bodynerd on facebook who posts the most awesome “Wednesday Musings” about her observations while working with clients, but I didn’t actually know who she was. In February, we attended the same seminar and I finally got to meet Jenn! The following weekend, I was in a marketing seminar hosted by the awesome peeps over at Udaya, and they urged us to find guest bloggers. Shortly thereafter, Jenn boldly commented on one of my facebook threads, questioning a particular transition we commonly encounter in yoga classes. She had I shared a similar view and had an interesting dialogue right there in the thread. Turns out, she writes a fantastic blog of her own. I asked her to turn our thread into a blog so I could share it here, after which we go into a short Q&A to somewhat recreate our original conversation.

Jenn Pilotti has an M.S. in human movement from A.T. Still University and a B.S. in exercise physiology from UC Davis. She holds several certifications, and is a long time yoga practitioner. She owns a personal training studio in Carmel, and regularly lectures on topics related to health and wellness. More information about Jenn can be found at www.bewellpt.com. Be sure to subscribe to her blog!

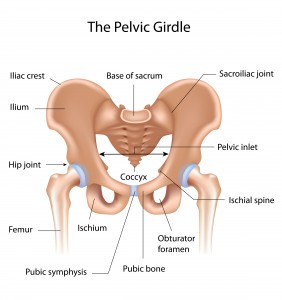

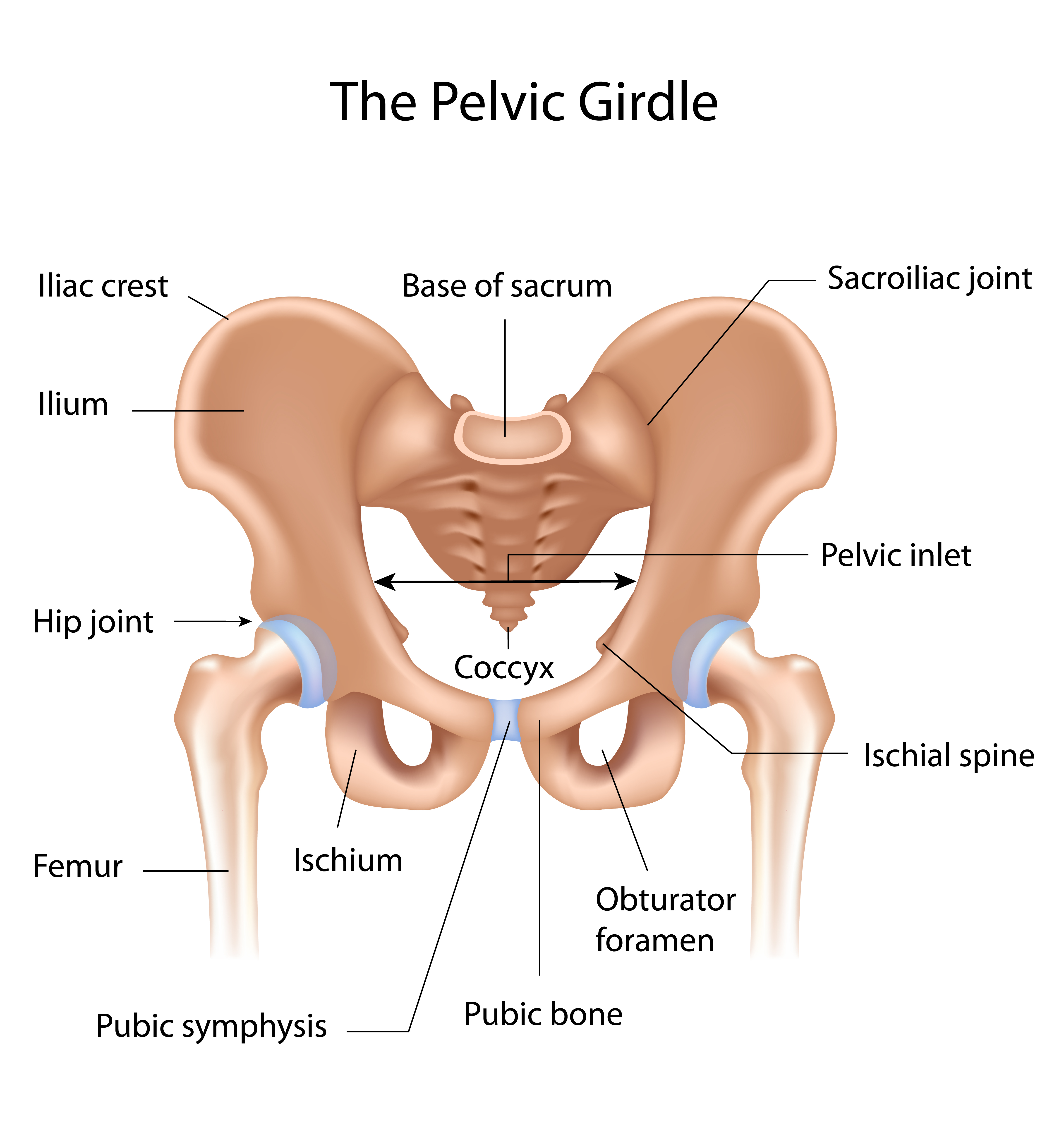

The hip joint, a.k.a the femoralacetabular or FA joint because it’s where the femur meets the acetabulum, is a ball and socket joint, and allows for movement of the femur in all directions. Around the periphery of the acetabulum, or the ridge of the socket, is a cartilaginous structure called the labrum [1]. It is mostly avascular, meaning it doesn’t get a lot of blood. Additionally, there are pain fibers on the anterior (or front) portion of the labrum. The labrum helps stabilize the hip joint and in the case of repetitious rubbing, can be torn and cause pain [2]. The lack of vascularization means healing is often difficult.

(image by Shutterstock)

(image by Shutterstock)

There are three major ligaments associated with hip stability. The iliofemoral ligament is a Y shaped ligament and tightens with hip extension. The pubofemoral ligament is located to the inside of the hip capsule and tightens with extension and abduction, and the ischiofemoral ligament also tightens with extension. When the hip is flexed, there is an increase in capsular laxity.

When you look at the structural anatomy of the hip joint, it becomes obvious why during asana practice it is important to maintain structural integrity and not “hang out on your ligaments,” especially when the hip is flexed. When the ligaments become overstretched and the muscles in the posterior aspect of the hip lack the strength to hold everything in place, this can become a problem for the deeper structures of the hip.

This is also what makes the transition from virabhadrasana I-virabhadrasana II (Warrior I-Warrior II) particularly tricky.

Warrior I is a closed hip asana, with the pelvis facing forward and the shoulders and hips in line with the front knee. (Interestingly, in “Light on Yoga,” Iyengar states this pose is particularly strenuous and should not be held for a long period of time. Of course, he also says it is good for reducing fat around the thigh, and we all know that doesn’t really work).

Virabadrasana II, on the other hand, is an open hip position with the shoulders and hips facing the side of the mat. These two different hip positions place different demands on the front hip joint. In the pictures below, you can see the femur rests in the socket differently in these two poses. If someone lacks good lateral hip activation on the front leg in Warrior I, when the hip opens from Warrior I to Warrior II, there is a good chance the femur position may be more forward in the joint, placing the surrounding structures of the hip joint at risk for overuse, specifically the labrum and ligaments.

Virabhadrasana I (Shutterstock)

Virabhadrasana II (Shutterstock)

Many of the people attracted to yoga asana practice, particularly at the more advanced levels of practice, are quite mobile, and some fall into the category of hypermobile. A practitioner that is hypermobile may find understanding lower limb joint position challenging [2]. If you lack proprioceptive awareness of your front leg during this transition, this could be problematic later. Researchers, in fact, suspect one of the non-traumatic causes of hip instability is repetitive external rotation with axial loading – which is what our front leg does as we move from virabhadrasana I- virabhadrasana II [3]. When you couple this with the high joint moments of force that already exist in Warrior II, performing this transition repetitiously may lead to wear and tear on the hip joint [4]. This might not be an issue if you are spending time specifically strengthening the hip, but a better option may be to limit how many times you perform this transition during class and make sure to maintain structural integrity of the hip joint by keeping a subtle sense of awareness in the lateral hip.

It is worthwhile to note that for repetitive use injuries, often the subtle warning signs are ignored. If you experience pinching in your hip during malasana (Garland Pose or deep squat), virabhadrasana I, virabhadrasana II, or versions of anjanayasana (low lunge with the back knee down), make sure you don’t ignore and push through. Get assessed by a medical professional and, if cleared to perform asana practice, make sure postures like pigeon are performed more in a strengthening way unless fully supported by bolsters.

Even if you don’t experience pinching, if you are in a class that is utilizing the Warrior I-Warrior II transition repeatedly, take the time to lift up out of Warrior I and take load out of the front hip before coming back down into Warrior II. If you teach, rather than go through Warrior I directly into Warrior II over the right leg, perform Warrior I on the right, lift up, turn, and perform Warrior II over the left leg. There is no reason to work through pain, and taking the time to create balanced strength and mobility in the body might prevent long term issues later.

Q&A with Jules:

Jules: In your blog you made this statement: “Make sure postures like pigeon are performed more in a strengthening way unless fully supported by bolsters.” I totally agree with this, but I think the current yoga culture may not know what that looks like. We have morphed Single Pigeon Pose into a floppy, stretchy, feel good pose. As you mentioned above, there is an increase in joint capsule laxity during flexion. In my teacher training, we spend considerable time noting that even Light on Yoga doesn’t show Pigeon Pose a floppy forward bend. It’s an active upright posture that prepares you for a split leg backbend. Those lateral hip muscles in the front leg should be trained to develop enough strength to support the backbend in this joint position. I have all sorts of creative ways to train those hip muscles, but I’ve seen a video of yours that I think the readers would love. Could you post it here and comment as well?

Jenn: Absolutely. Here is the video:

Jenn: The interesting thing about yoga is we are taught we need to open everything up to experience the fullest expression of the pose. This sense of openness or flexibility needs to be countered with a sense of strength for the neuromuscular system to effectively move into end range positions without alarm bells going off or compensations to occur. The great thing about yoga is we move in a slow, controlled manner, giving us time to focus on strength between transitions, figuring out how to slow a movement down (like stepping forward into lunge), and emphasizing the strength in an asana, rather than surrendering to the sense of stretch, which I know you have discussed in your blog before. Yoga can really be a strength based practice if the intention is shifted to make it so.

Jules: I think we both agree that in general, yoga is pretty awesome. I have my opinions, but I’d like to hear yours. What is it about our current state of yoga asana that has sparked smart conversations (like this one) about injury mitigation?

Jenn: Yoga is pretty awesome (despite the fact that I am not very good at it. I think that’s why I keep coming back to my mat). Unfortunately, the current state of advanced yoga practitioners seems to be one where there is a high incidence of little chronic aches and pains. It is my opinion that in order to perform a regular, challenging asana practice, supplemental training needs to be done. Targeted work on areas where one has instability or inefficiency (not the same thing), and addressing chains of muscles in a dynamic fashion can begin to give us the strength and mobility to perform a 3-4 day/week asana practice. In a society where even active people sit a fair amount, we need to take the time to become more embodied, not just through yoga practice, but through developing strength, understanding how our joints move on an individual basis, and building strength through a variety of ways, not just through yoga.

Jules: Cheers to that. #yogaeverythirdday Or, at least if you’re going to practice #yogaeverydamnday it should incorporate variations of postures that do exactly what you suggested. I think I just decided on my next blog topic.

Jules: I understand you want to credit your teacher for inspiring this blog.

Jenn: Yes! A special thank you to Coral Brown for piquing my curiosity about this particular transition during teacher training.

Jules: I love it. So, while we are at it, I will thank my teachers as well. Thank you Leeann Carey for my training in yoga therapy and thank you Gil Hedley for holding the most profound dharma-esque talks I could ever ask for.

_________________________________

[1] Larson, C.M., Swaringer, J., & Morrison, G., (2005). A review of hip arthroscopy and its role in the management of adult hip pain. Iowa Orthopedic Journal, 25, 172-179.

[2] Smith, T.O., Jerman, E., Easton, V., Bacon, H., Armon, K., Poland, F., & MacGregor, A.J., (2013). Do people with benign joint hypermobility syndrome have reduced joint proprioception? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatology International, 33(11), 2709-2716.

[3] Smith, M.V., Sekiya, J.V., (2010). Hip instability. Sports Medicine & Arthroscopy, 18(2), 108-112.

[4] Man-Ying, W., Sean S-Y., Y., Hashish R., Samarawickrame, S.D., Kazadi, L., Greendale, G.A., & Salem, G.A., (2013). The biomechanical demands of standing yoga poses in seniors: The Yoga empowers seniors study (YESS). 13(8).

Extend Your Learning: Advanced Yoga Teacher Training with Jules Mitchell

This program is ideal if you have an interest in biomechanics, principles of exercise science, applications of pain science, neurophysiology, and stretching. These themes are combined with somatics, motor control theory, pose analysis and purpose, use of props for specific adaptations, pathology, restorative yoga, and intentional sequencing.

You will learn to read original research papers and analyze them for both their strengths and their biases. Critical thinking and intellectual discourse are central components in this training, which was designed to help teachers like you navigate through contradictory perspectives and empower you with education. Learn more >

Thanks for the great article. Although I completely concur with the subject, I find an even more alarming transition to be Warrior III to half Moon. With all the body’s weight on the femoralacetabular joint, I can’t believe teachers allow students to perform this. One is basically bone-on-bone during that transition. I was just about to write an article on this subject myself! Thanks for writing this great stuff that all asana teachers and students should know.

I do take issue with one small part of your Q & A. You say you are not “good” at yoga. I submit that there is no such thing as “not good at yoga” as (a) one can’t really “do” yoga because it’s not a verb or a sport, it’s something at which one (hopefully) arrives “union/yoke/joint” and (b) being “good” at something is relative. I’d say that if you are practicing what you preach, you are probably quite “good at yoga” due to the diligence in which you practice your asana. If you mean being “bendier,” then being good at that is somewhat of an oxymoron. Why would one need to be good at being flexible when yoga is about the mind-body connection? Consider the contortionists in Cirque Du Soleil – are they good at yoga even though they’ve never practiced? Once again, thanks for writing. Namaste.

As someone who went to the brink with a hip labral tear and was brought back again by Jules, I can’t say how much I appreciate what you both do. I love the comment about how yoga can be a strength building practice if only we bring that intention to it. I have been bringing all that Jules has taught me into my yoga flow classes, going at my own pace and bringing these strengthening and awareness techniques into it, and my yoga practice is SO much more healing and fulfilling because of it. (And I get a kick ass workout that nobody else in the class is getting, I’d warrant). It’s like blinders have been removed and I can’t believe people can practice without getting hurt when they don’t know this stuff. SO IMPORTANT. THANK YOU.

Oh…and I LOVE this little hip strengthening sequence. Quick, to the point, and different enough than stuff I’ve already been doing to mix it up nicely. My hips felt very well placed afterwards. Namaste.

Great article and thanks for the comment, Adam – I was wondering about that transition also as I read this article.

Adam and Natalie,

http://www.julesmitchell.com/ask-jules-why-is-it-so-bad-to-transition-from-neutrals-to-externals/

For the Warrior 3 > Half Moon transition.

Hi Jules,

Just read your entire blog and so happy to have found it. Thank you for all the research you’ve done, for putting the latest biomechanics relevant to yoga practitioners/teachers in layman’s terms..and for recognizing that this is all a work in progress. Fodder for my own teacher training in which I am very committed to presenting as evidence-based material as possible.

I have two questions:

1. Do you think there is a compelling reason to engage in passive, supported, stretching, resulting in creep (targeting joint capsules plus ligaments/tendons/fascia) in aging bodies (over 40? 50?) as a way of maintaining the mobility we already have with the assumption that all of our tissues are drying up and shrinking as we get older? Asked in another way: What happens to our fascia as we age, and does passive stretching become more relevant in older bodies?

2. You have yet to present the benefits of a stretching practice…neurologically? chemically? As I see it yoga is the only modality where we are asked to take our joints through their maximum possible ROM for health and wellbeing (skirting injury). Dance, Martial Arts, Acrobatics all have other objectives… Given the risks, what are the benefits of having access to one’s full ROM in every given joint structure? Or what are the benefits of the stretching process if the end result is full ROM?

Hi Valerie,

1. Passive stretching has his benefits, but changing the viscoelastic properties of tissues isn’t one of them – at least if you consider the data of recent years. As we age our tissues tend to weaken, so I would recommend active stretching and loaded movements.

2. There’s a lot in this question not sure where you’re going with it. Yes, neurological and chemical factors are to be considered. I discuss them both in my lecture. Being able to move joints through full ROM does not skirt injury. Full ROM is only beneficial if you have control over every joint positions. If joint friction is a cause of limited ROM, all the stretching in the world won’t help ROM.

Hope that helps! Thanks for stopping by and commenting. Hope to see you in a lecture soon!

Love,

Jules

Can you please explain the difference between instability and inefficiency. Thanks

So Happy! Thank you! Didn’t mean skirting…meant barring injury. So the goal is to have muscular control (strength) in every possible joint position that does not over stress the joint. I will join a lecture! Wanna hear more about joint friction:) Thanks again!