My friend and colleague, Jenn Pilotti, delivers again with a guest blog on an important topic for yoga teachers. I actually find the dialogue she has begun here to be so essential to education for yoga teachers, I have a hashtag for it: #thepigeonconversation

As usual, and in my typical guest blog format, you’ll find a casual conversation between me and Jenn at the end. We hope you enjoy the read!

The sciatic nerve, piriformis syndrome, and why pigeon pose might not always deliver relief

Yoga has long been touted as a healing practice. The ashtanga primary series, for instance, is

referred to as “yoga chikitsa,” or yoga therapy, because of the cleansing and toning effect it is believed to have on the body and mind. However, as more and more people suffer from various aches and pains, including sciatica, is it possible the postures we think of as healing might need to re-examined?

It will come as no surprise that yoga appears to have a positive impact on those with low back pain; whether or not it’s any more beneficial than other forms of exercise has yet to be determined (1). Yoga does, however, appear to be as effective (if not more) on improving quality of life in individuals with breast cancer, heart failure, and diabetes. Yoga also appears to be an effective ancillary treatment for trauma disorders, such as PTSD, anxiety, and depression (2).

But what about things the internet promises yoga will cure, such as sciatica?

When I ran a PubMed search for yoga and sciatica, I found four peer reviewed journal articles:

- The first showing yoga had no adverse effects on sciatica and, in fact, led to a self reported reduction in pain (3).

- The second found yoga asana was effective in reducing pain and improving mobility in individuals suffering from sciatic symptoms (4).

- The third found individuals suffering from conditions such as sciatica, headaches, migraines and strokes were more likely than those without neurological conditions to explore mind body therapies, including deep breathing, meditation, and yoga. The authors concluded there was a lack of high quality studies demonstrating the efficacy of these interventions on neurological conditions, with the exception of headaches, where mind-body therapies appeared to be effective in reducing the frequency (5).

- The fourth concluded the only therapies with good quality evidence for efficacy in chronic back conditions were cognitive behavior therapy, spinal manipulation, exercise, and interdisciplinary rehabilitation. In acute low back pain, the only therapy with good quality evidence of efficacy was heat. Yoga did not have enough high quality evidence to determine whether or not it was beneficial in helping sciatica symptoms (6).

Compare this to a Google search of sciatica and yoga. Google generated 502,000 hits. The first page is filled with articles promising to cure sciatica with 6 (or 7, or 8) simple yoga poses.

It appears there is a slight discrepancy between the research and what consumers are being promised.

This isn’t to say yoga doesn’t help with sciatica. As noted in the studies above, the early research appears promising. It does, however, mean re-examining the guarantee of yoga as a “cure” (fourth Google hit was a YouTube video entitled “yoga to cure sciatic pain”). Exactly which asana are consistently promoted on the path to the sciatica cure? Variations of pigeon pose, gomukhasana, and ardha matsyendrasana.

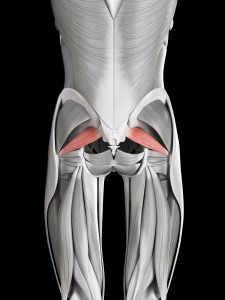

I am hopeful that by shedding some brief anatomical light on the sciatic nerve, documented causes of sciatic nerve pain, and how this may or may not relate to the piriformis (which is what the postures most often listed also stretch), we as yoga practitioners can be a little more careful in our words and perhaps approach back pain with a more discerning eye.

(image by Dreamstime)

(image by Dreamstime)

First, a little bit of anatomy. The sciatic nerve innervates the posterior (back) portion of the thigh (7). It is comprised of spinal nerves coming from lower lumbar vertebrae and sacral vertebrae, specifically L4-S3. It is important (as all nerves are), and exits the pelvis below the piriformis via a hole named after it, the greater sciatic foramen. While it does not supply any of the structures in the gluteal region, it does supply branches to the hip joint and muscular branches to the hamstrings (8).

Interesting tidbit: the sciatic nerve branches into two nerves, the common peroneal nerve and the tibial nerve, after it exits the greater sciatic foramen near the upper angle of the popliteal fossa (posterior aspect of the knee) in most people. However, because we are humans and variability exists, sometimes that’s not how the nerve divides. In a small percentage of the population it divides higher up the back of the thigh or within the pelvis (7). The sciatic nerve also can be variable in where it exists in the pelvis, usually exiting below the piriformis, but sometimes above or even through the muscle, leading researchers to speculate this might be a cause of piriformis syndrome.

(image by Dreamstime)

(image by Dreamstime)

The next logical question is what exactly is piriformis syndrome and how does this relate back to yoga? I am going to (quickly) explain the function of the piriformis, what this has to do with sciatica, and how the interpretation of piriformis syndrome as a cause of sciatica has seeped into mainstream culture.

The piriformis is considered one of the deep six hip stabilizers. Its functions vary, based on the position of the femur. The attachment points for the piriformis in the pelvis are the anterior (front) aspect of the sacrum (S2-S4), the front capsule of the SI joint, the posterior inferior iliac spine, and sometimes the upper part of the sacrotuberous ligament (that variability thing again), (9). It travels out the pelvis via the greater sciatic foramen (sound familiar?) and attaches to the greater trochanter of the femur. It’s innervated by the ventral rami of L5 and S1. Hopefully, the parallels between the paths of the piriformis and the sciatic nerve are beginning to make sense.

When the hip is flexed, the piriformis internally rotates and abducts the hip. When the hip is neutral, the piriformis externally rotates the hip (10). While walking, one of the main roles of the piriformis (along with the gluteus medius) is to control the rate of hip internal rotation (11). Basically, the piriformis works with several muscles to both allow for hip movement and stabilize hip movement. How well it does this is based on many different things that are outside the scope of this blog; suffice to say, like most things pertaining to the human body, it’s not quite as simple as “the piriformis does this.”

It’s more like, “the piriformis does this if the pelvis does this and the lumbar spine does that, and the thoracic spine moves that way,” or, “the piriformis does this if the femur does that in the pelvis based on the way the foot hits the ground.” There are other variations of this theme, but you get the idea. We are an integrated system; one of the beauties of yoga is it does not isolate movement down to one joint or muscle. Shapes in the form of asana are used to express this integration. Postures like pigeon and ardha matsyendrasana explore externally and internally rotating the hip which, depending on how they are taught, will allow the practitioner to access sensation through hip.

So back to how this pertains to the sciatic nerve and the obsession with the piriformis as acause. One of the theories that exists regarding pain in the buttocks that radiates down the back of the leg is the pain is caused by compression of the sciatic nerve through or around the piriformis muscle, aka piriformis syndrome, which I mentioned earlier (12). It is estimated piriformis syndrome is the cause of radiating nerve pain in 6% of individuals seeking medical attention for sciatic nerve pain (13). That leaves 94% of individuals with sciatica experiencing symptoms for a reason not related to the piriformis, and it is estimated based on studies that 85% of sciatica cases are related to a disc disorder, usually at the level of L4-L5 or L5-S1 (14).

Other causes of sciatica include: osteoarthritic impingement, synovial cyst at facet joint, tumors, endometriosis, vascular impingement, and hip fracture. The point of all of this is it is impossible for us as yoga teachers to know what is causing someone’s sciatic symptoms and it is even more impossible for us to predict with any level of certainty that specific asana are going to make it better. In fact, it would be prudent to state clearly here that determining the cause and selecting a treatment are both beyond our scope of practice as yoga teachers.

Where does this leave the yoga practitioner working with a student suffering from sciatic nerve pain looking for relief? First, make sure the individual is cleared from his physician to begin an exercise program. If you have a good rapport with the doctors in your area and they refer to you regularly, it is entirely possible the student will walk in with MRI results in hand. If you are comfortable with anatomy, this can be extremely helpful when dealing with nerve pain because it tells you what positions should be avoided. One of the many individuals I worked with suffering from sciatic nerve irritation showed up with her MRI results. As I read through them, I was a bit surprised at the level of stenosis in her thoracic spine. When I asked her how she obtained the initial injury, she shared it was in a yoga class during a twisting pose. While this was in no way the fault of the yoga, looking at her MRI it was obvious twisting postures, such as ardha matsyendrasana were not good choices for her. In fact, most of the twisting asana usually recommended for sciatica don’t work for her because of her anatomy. Fortunately, within 2 months, her low back and sciatic nerve pain were completely gone.

Which returns us to the question of how do we as yoga teachers safely work with these sorts of issues? Open communication is extremely important. Make sure the student is comfortable with the idea of ahimsa and understands the goal is not to experience an increase in pain or nerve sensation. There is frequently a disconnect when working with individuals suffering nerve pain regarding what is helpful and what is aggravating, so working at a slow pace and not covering too many asana in a session gives the student time to absorb the practice, develop interoception, and observe the physical and mental state after the practice.

In the study I mentioned in the very beginning that showed improvement in sciatic nerve symptoms after a four week asana practice, the asana intervention was extremely simple. Participants practiced two postures, four times, followed by deep breathing and relaxation, for a daily practice of 20 minutes (4). The asana used were variations of salambasana and bhujagasana, neither of which involve internal or external rotation of the hip joint. This type of sequencing allows the student to find the balance between sthira and sukha. Developing an internal awareness of the physical self can be hugely beneficial for self awareness of daily movement patterns and habits.

A sense of self awareness provides the portal for change to begin to take place. The yoga practice enhances this type of awareness and teaches us things like, “I grip my jaw when things get challenging,” or “I hold my breath when I am experiencing stress.” These little observations can add up to large changes in someone struggling with sciatic symptoms.

When developing a sequence for sciatic pain, understand that what works for one person might not work for someone else because the sources of the sciatic pain might be different.

I have a client that struggled with daily sciatic nerve pain for 5 years before she began working with me. Very, very slowly, I introduced different movements into her program. The one thing that still provokes pain is supine hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation, so we don’t do that. As a result, reclined pigeon is not a good choice for her. (She practices yoga, and simply avoids the hip openers when they are taught in class.) She now has days where she is completely pain free, and I am hopeful that eventually she will be able to do reclined pigeon without provoking symptoms. Her sciatic nerve pain comes from an injury related to a fall. Five years of pain doesn’t go away over night; by working slowly, methodically, and with a sense of mindfulness, she has been able to make significant improvements in pain level, strength, and mobility.

My point (and yes, there actually is a point), is we can’t look inside someone to know what’s going on, either emotionally or physically, nor should we try. It is outside our scope of practice. In yoga, we use the asana as a bridge to teach self-awareness and mindfulness.

Maybe the exact asana matters less than the understanding it brings, including the ability of the student to reflect on what seems to help and what seems to hurt.

While researching this blog, I was sitting on the ground outside my studio, with anatomy books spread out. A gentleman stooped down, curious about what I was studying. I explained I was writing a blog on yoga and sciatica. He became very animated as he told me about his lumbar fusion and the role yoga played in his healing process. He then folded forward into a standing forward fold to demonstrate his mobility. Forward folds feel great for him. However, backbends feel less great, so he does fewer of those. It is this self-regulation we can hopefully teach our students to empower them on their paths to lives filled with diversified movement, mobility, and awareness.

Q & A with Jules

Jules: Awesome contribution to the yoga community, as always, Jenn. We all thank you! I’d love to explore some of these themes further with you if you don’t mind.

Jenn: Yes, of course! Not only does reading through research and writing about anatomy and its applications make me happy (a thrill of a dinner date, I know), but exploring these types of concepts and critically thinking about working with people in a yoga/movement setting is a bit of a passion. Thank you so much for allowing me to be a part of the conversation.

Jules: This is why we’re friends. 🙂 Let’s start with the interesting fact that only 6% of sciatica cases reported in the literature are suggested to be due to the piriformis compressing the nerve. Do you think that the mainstream so readily adopts the the nerve compression theory because it’s easy grasp? Yet if study anatomy you will see that the sciatic nerve is a thick robust structure and the relatively miniscule piriformis appears to be an unlike offender. In fact, nerves travel through muscles all throughout the body without compression syndromes. It seems illogical for the largest nerve to be the one with the weakest defense against muscle tissue. Thoughts on this?

Jenn: I think people have a desire to understand pain and seek a logical, pathomechanical solution to the reason they are experiencing things like sciatica and yes, I think a “pinched nerve” makes sense to people. “A muscle is pinching my nerve. This causes me pain. If the muscle is no longer pinching my nerve, my pain will go away.” The trouble with this is a) the anatomy is, as you noted, more complex than that and compression doesn’t occur in other parts of the body and b) pain is more complex than that. But people want an immediate answer and solution. This is why I think interoception and svadhyaya are so important. Self awareness and mindfulness give us knowledge about how things like emotion and habitual tension patterns can affect our entire system. Like me, you work with students suffering from a myriad of back conditions. What has your experience been in working with sciatica?

Jules: My experience in working with sciatica has been that classic stretches often aggravate the nerve further. My approach has thus evolved into promoting confidence of movement, variability, pain education, developing interoception, and (gasp!) strengthening – all of which are what I consider essential to an asana practice.

Jules: Another issue I have with internet solutions to sciatica is the idea that stretching the offending piriformis muscle will relax it and, therefore, lessen the compression. My opinions on stretching aside, let’s just pretend that stretching the piriformis muscle is what we want our clients to do. I don’t think the pigeon stretch is even the best stretch for the piriformis because in many students the superficial glute max will be the limiting tissue in that pose (not to mention the often overlooked adduction required to target the piriformis more effectively). And you noted that the piriformis doesn’t innervate the glute max. So we aren’t even target the tissue we are intending to target. Comments?

Jenn: Lol, I completely agree with this, on many levels. When I first delved into the anatomy of gait, in graduate school, I was confused as to why flexion, abduction, and external rotation (the figure 4 stretch) were being used to stretch a muscle that requires adduction to be stretched. I do think pigeon targets the posterior capsule of the hip effectively, just like thread the needle does for the shoulder, but if the goal is the piriformis, it seems to me there are better ways to do it. I understand using gomukhasana and ardha matsyendrasana- at least there is an adduction component. Also, I find individuals with low back pain struggle with understanding the position of the pelvis in pigeon (we have all seen the flexible individual that flops into pigeon with the back leg and hemipelvis externally rotated. This shows up again in hanumanasana, obviously not an asana usually prescribed for back pain, but one that frequently shows up in modern yoga classes). You have a much stronger biomechanics background than I do. What are your opinions regarding the efficacy of pigeon to stretch the piriformis?

Jules: There are definitely more effective ways of targeting the piriformis. Yes, the piriformis may technically lengthen somewhat as the hip continues to flex. But it sort of just goes along for the ride and most people will most likely be stopped by the superficial structures, or as you mentioned, perhaps the deeper joint capsule. As usual, I love to refer back to orthopedic tests. The piriformis test is done prone, knees bent, with the hips in neutral (extension) and internally rotated (not even close to resembling hip flexion, abduction, and external rotation). That said, just because it’s called the piriformis test, it doesn’t mean much. It may actually be giving you more information about a joint capsule restriction or positional interference rather than an unyielding piriformis. But now we’re starting to touch on some much more complex topics which we’ll save for our next dinner date.

Jenn Pilotti has an M.S. in human movement from A.T. Still University and a B.S. in exercise physiology from UC Davis. She holds several certifications, and is a long time yoga practitioner. She owns a personal training studio in Carmel, and regularly lectures on topics related to health and wellness. More information about Jenn can be found at www.bewellpt.com. Be sure to subscribe to her blog!

_____________________________________________

- Kelley, G.A., & Kelley, K.S., (2015). Meditative movement therapies and health-related quality-of-life in adults: a systematic review of meta-analyses. PLoS One, 10(6), 1-33.

- Macy, R.J., Jones, E., Graham, L.M., and Roach, L., (2016). Yoga for trauma and related mental health problems: a meta-review with clinical and service recommendations. Trauma, Violence, Abuse. pii: 1524838015620834. (Abstract only).

- Monro, R., Bhardwaj, A.K., Gupta, R.K., Telles, S., Allen, B., & Little, P., (2015). Disc extrusions and bulges in nonspecific low back pain and sciatica: exploratory randomised controlled trial comparing yoga therapy and normal medical treatment. Journal of Back & Musculoskeletal Rehabilitation, 28(2), 383-392.

- Singh, A.K., & Singh, O.P., (2013). A preliminary clinical evaluation of external snehan and asanas in the patients of sciatica. International Journal of Yoga, 6(1), 71-75.

- Erwin, W.R., Phillips, R.S., & McCarthy, E.P., (2011). Patterns of mind-body therapies in adults with common neurological conditions. Neuroepidemiology. 36(1), 46-51.

- Chou, R., & Huffman, L.H., (2007). Nonpharmacologic therapies for acute and chronic low back pain: a review of the evidence for an American Pain Society/American College of Physicians clinical practice guideline. Annual Internal Medicine, 147(7), 492-504.

- Adibatti, M., & Sangeetha, V., (2014). Study on variant anatomy of sciatic nerve. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(8), 1-12.

- Moore, K.L., Agur, A.M.R., & Dalley, A.F., (1995). Essentials of Clinical Anatomy. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

- Lee, D., (2011). The Pelvic Girdle: An Integration of Clinical Expertise and Research. FourthEdition. Churchill Livingston: Edinburgh.

- Keskula, D.R., & Tamburello, M., (1992). Conservative Management of Piriformis Syndrome.Journal of Athletic Training, 27(2), 102-110.

- Decker, M.J., Krong, J., Peterson, D., Torry, M.R., & Philippon, M.J. Deep hip muscle function during gait. Orthopedic Research Society. http://www.ors.org/Transactions/56/1929.pdf

- Cass, S.P., (2015). Piriformis syndrome: a cause of nondiscogenic sciatica. Current Sports Medicine Report, 14(1), 41-44.

- Arooj, S., & Azeemuddin, M., (2014). Piriformis syndrome – a rare cause of extraspinal sciatica. Journal of Pakistan Medical Association, 26(8), 949-951.

- Rooper, A.H., & Zafonte, R.D., (2015). Sciatica. New England Journal of Medicine, 372(13),1240-1248.

Extend Your Learning: Advanced Yoga Teacher Training with Jules Mitchell

This program is ideal if you have an interest in biomechanics, principles of exercise science, applications of pain science, neurophysiology, and stretching. These themes are combined with somatics, motor control theory, pose analysis and purpose, use of props for specific adaptations, pathology, restorative yoga, and intentional sequencing.

You will learn to read original research papers and analyze them for both their strengths and their biases. Critical thinking and intellectual discourse are central components in this training, which was designed to help teachers like you navigate through contradictory perspectives and empower you with education. Learn more >

Hi ladies! Great post Jenn, and great discussion. My boyfriend suffers from sciatic pain periodically (winter months are the worst, but it flares up sporadically) so I have a personal interest. While I of course assumed disc problems were one of the possible causes, I was actually shocked that the percentage of cases due to disc herniation was so high. I found a comparative effectiveness review of sciatica therapies [it’s a systematic review with meta-analysis – I know you love it! :)]: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24412033 I hope you’re able to click through to the full text of the paper.

So, the only interventions that showed significant effectiveness (according to this analysis) were: non-opiod pain medication, epidural injections and disc surgery. Interestingly though, acupuncture and manipulation (chiropractic) seem to show some modest effect. They found no evidence of effectiveness for exercise therapy, bed rest, or passive physical therapy.

I know a lot of people (my bf included) only turn to “allopathic” medicine as a last resort. But in the case of sciatica, it seems that it is most likely a medical problem that will probably only respond to medical intervention (surgery, injections, pain meds). So, what’s a reasonable amount of time should one spend on non-medical treatments, in the hopes that you’re one of the 6% or so for whom this is NOT a herniated disc (and assuming that the non-medical interventions ARE actually effectively targeting the tissues you’re trying to target?)

BTW, I miss your big brains! 🙂 Hope to see you again in the not too distant future!

Jules and Jenn – this is great blog and discussion – excellent advice!

And the complexity doesn’t stop here, but I think throwing the rest of this into a blog would make it rather messy – I think there are at least two other important points here – what is your definition of sciatica (and do the research studies use the same definition, and is this in line with what lay people and medical people call sciatica)? AND, what is the proposed mechanisms of the pressure from the piriformis muscle creating pain down the leg?

Sciatica is often referred to as pain in the leg that is coming from the low back region. Yet some researchers and some regulated health professionals are taught to differentiate sciatica that is referred pain (i.e., from any structure or organ in the blowback, pelvis and hip), from sciatica that is radicular pain (from irritation of the dura surrounding the spinal nerve root). This might be what the Arooj study was discussing – “sciatica nerve pain”.

We have long-blamed piriformis tightness on sciatica, yet there is no direct evidence of this. Could the piriformis be tight and have nothing to do with the sciatica (like some disc bulges and leg pain)? Could movements that potentially increase tension on nerve via the piriformis also alter the mechanical forces on the sciatic nerve or blood flow to the sciatica nerve’s neurons through stretch rather than compression? Do the treatments that we believe (and assess) to decrease piriformis muscle tension actually make a change in the muscle when there is also a decrease in the pain? (non-specific treatment effects might be the reason for the pain change, and we are notoriously inaccurate in palpatory changes pre to post treatment). And if we are talking about non-diffuse leg pain running along the path of the sciatic nerve, is there evidence that applying a mechanical force to peripheral nerve can in fact produce this (there is good evidence that radicular pain from irritation of the dura can do this).

None of this is intended to take away from what you wrote, but to add to it.

I love how you are challenging dogma!

Exactly. 🙂

When we were working on the blog, it was difficult to narrow the definitions of sciatica, piriformis syndrome, low back pain, etc. because as you mention, they are all over the place in the literature! In the end, I decided it was okay to keep it general since the target audience of this blog is yoga teachers and I don’t want to assume they all have an anatomy background that would warrant such an in depth discussion. Additionally, as someone who works in the trenches of the yoga community, I can attest that the general yoga rule of thumb is piriformis syndrome or disc complications. Of course, as you mention even those are insufficient as neuropathies get very complex, very quickly. And then there’s the pain component as well, as you very well know – that being your life’s work. Thanks for you comments and they do add to the conversation, absolutely!

And regarding the proposed mechanism for piriformis tension/compression. Your guess is as good as mine! Add what we know about stretching to the mix and the assumption becomes even weaker.

A great article- very informative- wish i had this info years ago – i am one of those people for whom pigeon pose eradicated my back problems, which ran down my left leg, looking like sciatica- when it seems it was some form of piriformis syndrome all along- i had been to numerous chiropractors, western docs, physical therapists etc all saying it was sciatica; i even had cortisone shots — i only knew that i was strangely attracted to pigeon pose once i started yoga despite how difficult it was for me – i only then looked up and learned about the piriformis muscle- i never had a yoga teacher push the pose as a cure- i just know it worked for me- interesting to know that i am in that 6%.-

Great article. Here is what I learned through my journey…. I hope it helps someone.

Piriformis muscle pain can come from weak glutes. People who have hip structural issues, can tend to compensate and use the piriformis muscle more to stabilize the femur. When this happens, the piriformis muscle can become hypertonic and it can compress the sciatic nerve. It can’t be overstated to keep glutes strong.

Other causes of piriformis pain, is from nerve compression in spine. The nerve gets compressed and sends signals to piriformis muscle to fire. Core strengthing can help ease this type of pain.

Sacroiliac joint dysfunction can also cause pelvis to not be stable and pull piriformis muscle. Core strengthing helps with that too.

Other people, can have piriformis muscle syndrome because the sciatic nerve runs through the piriformis muscle, or they have a large piriformis muscle that pinches sciatic nerve. There is anatomical variances in individuals. Any compression to this area, like sitting can cause sciatica. If this happens, it’s terrible! I had a piriformis tendon release and sciatic nerve neurolysis surgery. It s a very complex surgery and it can take a long time to recover from and should only be a very very last treatment option!!! It am one year post op and still recovering.

There is a Piriformis Muscle Syndrome (with or without Fibro) Facebook Group. There is lots of resources in the files section for people who suffer with this.

My biggest suggestion, is to have spine and hips looked at by doctors, to determine what the root cause of the pain is. The doctors should order MRI of pelvis and spine. If hips are an issue, they should order MRI with contrast and a MRA. If the hips and spine are not issues, there are nerve imaginging machines like MRN machines that can image the sciatic nerve to see where it may be compressed.

If you can determine what the roo cause of the piriformis pain, you can choose the proper treatment optio. If you treat the piriformis pain incorrectly, it can make it worse.

I hope this helps someone who is looking for why they may suffer with piriformis muscle pain.

I am not a medical professional, just a piriformis muscle syndrome suffer and try to help others.